- Home

- Bruce McCall

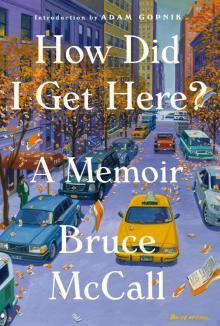

How Did I Get Here?

How Did I Get Here? Read online

Copyright © 2020 by Bruce McCall

Hardcover edition published 2020

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisher—or, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency—is an infringement of the copyright law.

Published simultaneously in the United States of America by Blue Rider Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Signal and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House Canada Limited.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: How did I get here? / Bruce McCall.

Names: McCall, Bruce, author.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20200190784 | Canadiana (ebook) 20200190792 | ISBN 9780771057168 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780771057175 (EPUB)

Subjects: LCSH: McCall, Bruce. | LCSH: Cartoonists—Canada—Biography. | LCSH: Artists—Canada—Biography. | LCGFT: Autobiographies.

Classification: LCC NC1449.M325 A2 2020 | DDC 741.5/971—dc23

Images 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9 are courtesy of the author.

Book design by Lorie Pagnozzi

Jacket art by Bruce McCall

Jacket design by Christopher Lin

Published by Signal,

an imprint of McClelland & Stewart,

a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited,

a Penguin Random House Company

www.penguinrandomhouse.ca

pid_prh_5.6.1_c0_r0

Dedicated to my brother Hugh

Contents

introduction by adam gopnik

Chapter 1

Be Careful What You Wish For

Chapter 2

Underground Artists

Chapter 3

Chronicles of Wasted Time

Chapter 4

Canada Trash & Tragic

Chapter 5

An Upgrade Called America

Chapter 6

Scared by Success

Chapter 7

A Thousand Moods, All of Them Somber

Chapter 8

America Discovers Satire

Chapter 9

Saturday Night Dead!

Chapter 10

Appalachia North

Chapter 11

Under the Covers

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Every life, experienced from inside, feels like a failure. Even Shakespeare, from the evidence of the sonnets, retired thinking that he had wasted too much time on all those popular plays (in retirement, he was going to focus on his poetry), while Mozart’s final frustrations were off the charts. Only a very few lives, however, benefit from an articulate underestimation of their own accomplishment, since they make us ironically aware of the actual processes of artistic triumph. All of which is an unduly fancy way of saying something simple: Everyone I know thinks Bruce McCall is a genius, except for Bruce, who hardly thinks he’s gotten much past dunce.

This is not disingenuous, on either party’s part. What we mean by “genius” is that he has a style, a vision, that is both instantly recognizable and entirely ineffable—it can’t be reproduced by anyone else—and also that the satiric points he lands in this unique style are always on the money. His marriage of a century’s worth of virtuoso commercial illustration styles with a first-class satiric imagination creates both delighted laughter and uncanny truth. Looking at what we have to call, since the 1980s, Trump’s New York—an insane place that looks plausibly real but hides its madness within it—well, only McCall has shown us its tall, slick, demented shapes.

Yet, reading this book, the reader comes away knocked sideways by the sheer painstaking study that led to the wild flights of surreal fantasy. Throughout, in describing his formation as an artist, he emphasizes skill, fidelity, mastery, truth. “Realism” is his principle and “detail” his watchword. From the first, one sees that McCall instinctively understood the great Surrealist principle: The more detail an image contains, the more dreamlike it becomes. Getting everything maniacally right drains mundane reality from a painting or drawing, and lets it enter into the realm of the visionary. A diagram is the most fantastic kind of image ever created. Reducing and describing—cutting away in cross sections and footnoting each labeled part—it overlays a wistful logic on the sheer chaos of actual life. The more encyclopedically detailed a car or a skyscraper is, the more unreal it seems.

This is very partially a perceptual effect—as McCall says, we all work with a varying failure of optical focus: we don’t see a world of even microscopically exact detail, except in illustration. But this perceptual effect is more a result of the way that the styles of illustration participate in desires even as they summon up descriptions—the realist illustration that McCall grew up on makes fantasies real (the car with the proportions of an aircraft carrier, the luxury motel on Mars) and in so doing makes the real fantastic. Not the least of the many pleasures of reading this, the second volume of autobiography he’s offered, is to see him for the first time lovingly inventory the great illustrators, almost all names unknown to anyone but aficionados, who influenced him. My own Google image search worked overtime to discover, and let me for the first time fully appreciate, such extraordinary figures as Robert Fawcett, with his tweedy atmospheric interiors; the astounding Art Fitzpatrick, whose Edenic images of Pontiacs with grilles as wide as a sixties expense account are hard to credit as anything except Pop Art parody advertisement (they weren’t); and above all the great Chesley Bonestell, the visionary science fiction illustrator, who showed a view of Saturn from the planet’s largest moon, Titan, as though it were a view across a fifties back fence. The imagery that fed Bruce’s style, we learn in this book, was not mass produced, but particular, made by masters.

But his underestimation of his own gift is completely sincere—all he sees, like any artist, is work and failure. Because of the aplomb of his cheerfully pessimistic and self-deprecating nature—not a contradiction, more a Canadian national trait—we can therefore learn something about how genius really operates, exactly through the strength of his self-denial. McCall tells us that he has taken as his subject for this book the nature of the “Little Bang”—the explosive interior moments in a life when suddenly an ordinary Joe becomes an expressive fountain.

And what McCall reveals here is the secret of all bangs, big and little. It is the capacity for commitment. To a degree that he himself hardly seems to understand is exceptional, in this beautiful memoir he recalls, hilariously, what feels like every landing place, every teacher, every drawing desk where he has worked—every assignment to draw a car, every boss whose generous appreciation helped, every job praising a long-forgotten Corvair or Corvette—and we learn from the journey that art is just work taken to another dimension of purpose. He isn’t trying to push the artisanal foundation out of his story, from his perch of a now-legendary New Yorker artist. He moves it to the very center, with an eye to how even a modest job can teach a major lesson. McCall persistently underrates his own gifts, the gifts that overwhelm his friends. But this modesty also presents a path, one of persistence and sanity. A lesson learned in two ways: both that mastery of a craft is a springboard to art, and that without a genuine appetite for art, craft becomes mere labor. He writes of a not-untalented colleague that “Rudy practiced art without being an artist. His was the perfect example of that approach. No other art form int

erested him. The richest artistic rewards—pride, satisfaction, a sense of achievement, the joy of creativity—were of zero interest to him. He didn’t have to set aside his artistic nature because he didn’t have one. Rudy was distanced from any emotional connection with his work, which liberated him from anxiety, second-guessing, and self-doubt. I envied this bastard relative of mental discipline, but not enough to emulate it.”

And then there is the gruff, acerbic generosity of his writing! Sentence after sentence rises up, not, as with some of us, in polished preening but in a style as distinctly disillusioned as it is painfully funny. As when he writes of his family’s fatal relocation from their first home in Simcoe, Ontario, to a nasty new apartment in gray Toronto:

On a sunny and cold Thursday morning in November 1947, the car carrying most of the McCall family from Simcoe to their new life in Toronto (a life, the kids expected, that would be a whirl of unending action, fun, and pleasure) trundled to the far side of the city and crash-landed on the dark side of Pluto.

Not that Pluto, but since it was a featureless wasteland with no signs of life and a distinctly alien atmosphere, it could have been . . . It sat on Danforth Avenue, a miles-long East End corridor lined with modest storefronts, used-car lots, greasy spoons, and off-brand churches.

Many good humorists might have arrived at “the dark side of Pluto.” There is a spark of genius about “off-brand churches.” Again and again in this memoir, we are knocked sideways by sentences that manage to combine a misanthropic refusal to overrate reality with a gentle urge to be generous to the generous. This is, as much as it is a chronicle of many bangs, a story of shared loyalties with wife and children and friends. McCall’s perpetual underestimation of his own capacities allows him to overstate those of his companions—he writes reverently of the legendary first crew of editors at National Lampoon, without stopping to think that the only one with a real legacy is the older, more watchful man now writing this book.

His alcoholic mother and unreliable father and many siblings who shared the ship with him are honestly but never cruelly described, and one is left again with the conundrum of genius: How does it rise from such resistant ground? The one truth seems to be that his parents, for all their faults, knew good writing from bad, had a standard of excellence (even unto subscribing to The New Yorker), and infected their children with that knowledge. An uncanny natural ability to discriminate—to see the world sharply and cleanly—seems, for all their unhappiness, to have been a core McCall family virtue, and, however hard won from life, remains a Bruce McCall singularity. No one sees what Bruce does the way he does. Now we are lucky he has created this plausible diagram of the mechanisms that connect eye to mind, and mind to hand, and both to heart.

—Adam Gopnik

My life, and my dreams of being an artist, began in Simcoe, Ontario.

Chapter 1

Be Careful What You Wish For

Colonel John Graves Simcoe delivered the first valentine card in North America. A century later, another colonel, James Sutherland “Buster” Brown, Simcoe born and bred, drafted Defence Scheme No. 1, the Canadian government’s secret 1921 plan to invade key U.S. cities in the event of war.

That about covers the claim to fame of Simcoe, Ontario. I was born there when it was a town of six thousand; now it’s more than doubled, a bedroom community for Hamilton and Toronto. Simcoe prospered with a rich agricultural base, and tobacco was the big industry when I was a boy. No Ontario town was ever nominated to be sister city to Florence, and there were good reasons why Simcoe was among the nonstarters. Scottish conservatism is as close to the opposite of Florentine culture as can be imagined. Piano lessons and church choirs sufficed as culture, which otherwise had no role in the life of the town.

Kids like me avoided Sunday school and regular church attendance. We were unwitting cultural morons who couldn’t miss what we never had. As did all heathens, we wallowed in an idyllic freedom. This got a huge boost from the Second World War, which removed innumerable dads and further loosened the controls on our behavior. Domestic life and disciplining kids became, by default, the duty of wives, and wives of that era seldom ruled households harshly.

The McCall family was big—five boys and, eventually, one girl: Mike, Hugh, me, twins Tom and Walter, and Chris. I attribute my lifelong shunning of group activities to this. My antipathy took a brief time-out when I was suckered into Lord Baden-Powell’s Boy Scouts as a Cub, at the bottom of a hierarchy of ranks not unlike the arrangements in the Vatican. Boy Scouts patiently climbed up in modest increments: at the summit stood the Sea Scouts, as elite as the King’s Mounted Household Guards. I never saw a Sea Scout. I still suspect they were a gaudy invention, like Jesus, to keep all Boy Scouts striving.

I salivated when I landed on the Sea Scouts section of the official Scouts catalog. What greedy kid wouldn’t want that inventory? There were silken neckerchiefs. An over-the-shoulder leather Sam Browne belt. A steel canteen. A second belt around the waist, its clasp ingeniously mating two halves to form the Boy Scouts escutcheon. A small leather case clipped to the belt for fishing lures, small change, the odd whistle or rubber band. A hornpipe dangling from the same belt. Over the left shoulder, a set of semaphore signaling flags in a cylindrical leather case. There were pockets and flaps on the official Sea Scout shirt. Binoculars on a strap slung around the neck. Knee socks. A pair of waterproof Sea Scout brogans. Sewn onto the shirtfront and sleeves, resembling a horde of caterpillars, were cloth Sea Scout badges of merit: bed making, swimming, diving, drowning-cat rescue, tree felling, completion of an anti-seasickness course. Badges commemorating a fire extinguished, a torpedo assembled, a torpedo disassembled. And in the Sea Scout model’s hand, a silver whistle so powerful that when blown in Cairo it could be heard in Johannesburg.

Only the sons of mining company CEOs, arms dealers, and senior officers of secret banks could afford the complete Sea Scout uniform. I grieved for my fundlessness: my bilious-green, beanie-like peaked cap, cut to the pattern of every English public school boy’s cap since Tom Brown’s School Days, was my only item of Cubs regalia.

Ill fortune soon proved good fortune shortly after my enthusiasm for Lord Baden-Powell’s mild outdoor adventuring, feeble at the start, crashed. Our pack leader was exposed as a pederast and fled town on his Harley-Davidson with sidecar. I hadn’t the money for Sea Scouts gewgaws, and had already tired of sitting on my haunches in some ratty clubhouse, imitating a talking wolf by shouting, “A-Kay-LUH!” I slipped away. The Cubs cap hung around the house, a reminder of the dangers of joining up, until someone (me, legend has it) fed it one day to Billy Perkins’s dog, Tip.

* * *

■ ■ ■

The toys and tools of a happy boyhood circa 1943 demanded improvisation more than cash. While American kids feasted on tons of magnificent plastic junk, Canada couldn’t produce toys in wartime conditions beyond a handful of crude pot-metal Hurricanes. In Simcoe, fifty cents could buy the indiscriminate kid a tommy gun cut out of a chunk of wood that resembled a folded umbrella. Some of our improvisations:

The green steel pot Mother used to boil potatoes made a perfect Japanese Imperial Army helmet for Pacific jungle skirmishes in the lilac bushes.

The flour canister in the kitchen became a snowbound hell for the five plastic British soldiers—unfazed by their gas masks—sent to ambush Nazis in the wastes of Norway. Mother later discovered a Brit soldier buried deep in the flour, perfectly preserved.

Rich brown horse chestnuts, tied by strings to hankies, subbed for a band of Wehrmacht parachutists floating down from a second-story sunporch window to land on Crete.

A working cap gun bestowed prestige—and what felt like real killing power—on its owner. A mouth-made firing noise might spray a foe with spittle, but no firing noise from a human source could beat the three or four eardrum-puncturing bang-bang-bang-bangs in a cap-gun blast. A functioning gun cost an eight-

year-old partisan big money. A discarded cap gun retrieved from the battlefield, sans trigger and missing its fake-pearl celluloid handle, was as close as I ever came. Even rarer than a working gun were the dirty-red rolls of caps required to make it go bang! and emit an acrid aroma. These were forever in short supply. Maybe the army maintained an elite Cap Gun Brigade that claimed top priority—another damn casualty of wartime restrictions.

Weekly Saturday matinees ran war movies. Fifty-two weeks’ worth per year exhausted the supply, leaving us to sit through Durango Kid westerns, Boston Blackie detective junk, and the odd stale box-office hit, usually a musical. In retrospect, while certain Hollywood war flicks charged the imagination and lifted the soul, many were so cheaply made that footage of a World War I Spad was suddenly spliced into the frenzy of World War II dogfights. The best war movies were British: Target for Tonight, In Which We Serve, Five Graves to Cairo, et al.

Authenticity was the difference. They seemed more realistic than the stagey, broad American fare like Edge of Darkness or Desperate Journey.

* * *

■ ■ ■

Toboggans rocketed us down Simcoe’s steepest grade, off the first tee of the Norfolk Country Club. Snowshoes had been supplied by our boisterous cousins, the Stewart boys. I never got good at snowshoeing, which requires control and is more like walking hard than sliding along on a pair of skis. A bunch of skis reposed in the shadows but were seldom used, because Simcoe lacked the gradients they were meant for.

The substantial Jackson house sat on a hill directly facing our peeling stucco home across Talbot Street. Daredevil kids lugged their sleds up to the Jacksons’ front lawn, then dived downhill belly-first on the sleds. A Flexible Flyer, with glass-smooth steel runners, was the ride of choice. Victory went to the sledboy who eked out energy enough to keep his momentum as he reached Talbot Street and his path flattened out. He summoned the last erg of sledpower as he and his mount transected the slippery street and crossed the finish line in a controlled crash. On winter afternoons in Simcoe, darkness fell around four o’clock with an almost audible thud. Cars, headlights blazing, arrowed past. No walkie-talkies linked sledboy and headquarters. A shouted “Look out!” curbed—or tried to curb—sled and pilot as the operator mentally calculated time and distance, how many seconds would be left after the sled burst through the snow-shrouded bushes to lie squarely in the path of the onrushing Studebaker or Nash. That no sled ever collided with a moving vehicle was pure luck—and light traffic, is my theory.

How Did I Get Here?

How Did I Get Here? 50 Things to Do With a Book

50 Things to Do With a Book