- Home

- Bruce McCall

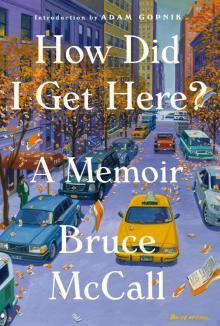

How Did I Get Here? Page 2

How Did I Get Here? Read online

Page 2

Hockey was a cultural signifier in Canada, and a further reason to not be American. The winter pastime made perfect sense: a sport for fans who adored the fast and graceful game while also secretly adoring the cretinous physical violence inherent in it. Canadian hockey fans had it both ways.

The national pastime was crucial to the Canadian sense of identity. Playing hockey was a ritual like the Japanese tea ceremony, except for the broken noses. Everybody wanted to play, but there was only one indoor rink in town, and it was devoted to skating parties for people who probably wouldn’t leave tracks of blood on the ice. Although Simcoe produced NHL players, few of them were graduates of ponds and backyard rinks. There were twenty wannabe players for every gifted one: How could anyone stand out when pickup games regularly placed thirty skaters on the ice—on both teams? For every ace—some lucky bastard who actually had a puck on his stick for a fleeting instant before vanishing under the human wave of defensemen—there were scores of wretches, drafted by neither team, who had no stick or who couldn’t find, borrow, or afford a pair of skates.

I came perilously close to being a hockey have-not. The solution, for me, was more like a part solution: in the pile of skates jumbled into a small mountain just inside the kitchen door in the McCall household at 101 Union Street (we moved there in 1942), I literally stumbled on a pair that fit. I hurriedly laced them up in case the owner happened by, and hobbled out in that weird wobble-walk even NHL players had to perform when negotiating a surface other than ice. I skated in circles, to demonstrate skills my older brothers had ridiculed me for. They ridiculed again. My newfound skates were for a girl. I should have detected that fact by looking at them: White. With tiny jingling bells.

The front lawn of 101 Union Street was big, but more important, it was level. Run a hose over a rectangular patch of dead grass long enough and by next morning there was a sheet of ice, a hockey rink (in Simcoe parlance, a hockey “cushion,” one thing it definitely was not). Snow was piled around the cushion as the boundary. What in November had been a gleaming white border carefully leveled to a uniform height was by early May a dark gray ruin of unevenly melting ice boulders.

* * *

■ ■ ■

Growing up during World War II made my contemporaries and me richer for the experience. I was four years old at the start and had just attained my first decade when they finally pinned and hog-tied Nazi Germany. There were twenty-point newspaper headlines, fire trucks marauding down side streets blasting their horns and jangling their bells, and a school shutdown. It was a day so hysterically noisy that no American would believe it was coming out of Canada.

That gaudy episode, in a culture allergic to overstatement, shook even a ten-year-old kid. My classmates, neighbors, and friends were glad to hear that Hitler was kaput—although that villain out of central casting left a gaping hole in our schoolyard pantheon of evil.

What the war meant to most Simcoe kids was the nonstop entertainment of movies, radio dramas, comic books, and Terry and the Pirates comic strips. One strip starred a freelance squadron of hero pilots who flew a matching set of Grumman Skyrockets, elevated by the sorcery of fiction from the real-life scrap heap to murderously fast, maneuverable fighter planes. The war was a tumultuous party, exciting enough to produce a prepuberty high. No wonder every shortpants warrior was secretly dreading a world at peace. What would life in Simcoe be without the drama of a really smashing war?

No more scrap drives, blood banks, Armistice Day parades. Worse yet for the platoon of neighborhood kids in volunteer armies, runty dogfaces all. No more campaigns fought in the war zone of the McCall grounds: thick bushes, copses, alleyways, the broad lawn favoring suicide charges by classmates–turned–Japanese soldiers screaming, “Banzai!” until mowed down by two Yanks-for-the-day and their imaginary machine gun firing from a nest obscured by a fanciful stack of sandbags. We fought an equal-opportunity war. British commandos or Afrika Korps tank drivers, Axis regiments bent on killing innocent civilians in Singapore or whatever Allied heroes were featured in last Saturday’s World War II matinee, against a handful of Axis rats stealthily nesting in the leafy umbrella tree edging the side porch that doubled as Allied HQ and my home. Nazis and Imperial Armed Forces constituted ninety-nine percent of all enemies fought and clobbered from the start to the finish of WWII.*

* * *

■ ■ ■

Dad was home on weekends from his job in Toronto from 1937 until he joined the RCAF and shipped overseas in 1941 at age thirty-one, when I was about six. He returned to Simcoe at thirty-three, battered by depression after a ringside view of the war, especially the death over France in mid-1943 of his closest friend, Wing Commander Chris Bartlett, on a night bombing raid. Nerves scraped raw, he underwent a brief recuperation at home, then went back to Toronto and a civil service job. Back to being an absentee father. A distant figure, anxious to see his brood grow—as long as we didn’t spoil his weekend golfing dates.

He was no hypocrite. He never pretended to be a doting dad. I hadn’t expected much and wasn’t disappointed. We barely knew each other, then and in the years to come. This mild estrangement, and his absence from my daily life, allowed the freedom I had come to take for granted to continue. He could radiate what felt like hostility, Mr. Murdstone barely tolerating David Copperfield.

His father, Walter Sydney McCall, would leave his family for months to go adventuring—i.e., gambling—turning up in parlors as far away as Texas. Dad’s strict moral code was probably fashioned at this point. He was not amused by his father’s exploits and held a grudge, spurning him in later years. And as his mother’s loyal defender-protector, he was steadfast until she died of cancer in 1938.

Dad married my mother, Helen “Peg” Gilbertson, in 1930. The core mystery remains: Why did they have half a dozen kids? Dad had to work 120 miles away to earn enough to make ends meet, starting a split family life that lasted from 1937 to 1947. By sheer numbers, six kids means family life. In spirit, we were barely a family. Particularly when it was clear that he didn’t even like kids. Mother paid the bill—six kids to care for, no money for anything except the kids, and the daily burden of heavy housework with no help. Worst of all, the darkness of loneliness. Drinking was a side door for a bit of relief. She was petite and not particularly robust to begin with. She was a living billboard for nice folk making themselves dizzy-drunk, and soon enough, full-fledged alcoholics. Neither Dad nor a town harboring its fair share of serious addicts lifted a finger to intervene. She graduated to alcoholism as a way of life, further tearing apart the pretense that this was a normal family raising normal kids.

Before he left Canada for his wartime stint in Yorkshire, Dad managed to send RCAF-style wedge caps to Mike, Hugh, and me. Captains of the Clouds was printed on both sides—he had been the RCAF liaison with the Hollywood team. They shot some footage nine miles away at the Jarvis Air Training base, and he attended the premiere in New York. Captains of the Clouds, led by Jimmy Cagney, saluted Canadian bush pilots. It failed to be nominated for an Oscar. It failed, period.

Thereafter, every few months a package arrived from overseas: war treasures from Dad. I snared a U.S. 8th Air Force shoulder patch. A rattling box full of Canadian and British military badges got snatched up before I could strike. A creepy weirdo from down Talbot Street managed to pry every one of them out of McCall hands for the equivalent of twenty-four wampum beads.

Dad had bequeathed a genuine RCAF “Mae West” life preserver to my siblings and me before marching off to war. Such prestige was showered on whatever McCall kid was bobbing around the municipal swimming pool in that balloon-like butter-yellow souvenir. That Mae West was coveted by its owners—but apparently not as much as by the footpad who one night stole across the lawn to grab the prize resting on the ground where it had been carelessly flung. It was never seen again.

Military affairs never inconvenienced Simcoe. Almost daily, Harvard and Fairey Battle training planes

howled overhead. Sunday afternoons a motley mob of airmen and soldiers in mufti wandered Norfolk Street, the town’s main artery, looking for fun. If they ever found it, they never spread the word. Hugh and I sometimes stayed at our aunt Eva’s house, situated diagonally across the street from the Governor Simcoe Hotel. On summer evenings we slept out on the porch—or tried to: across the way, the windows of the hotel’s lounge were wide open, the room packed with airmen, some of them freshly graduated pilot trainees, ready to muster for duty overseas.

Melancholia shouldn’t afflict innocent kids, so I must have been precocious: in the loud babble and the sing-alongs of ancient and familiar old marching songs, male voices raised and rolling into the dark summer night, I sensed a sadness beyond my ability to comprehend. This was my first overpowering feeling. That hotel lounge, with the babble of party talk and, stabbingly, the lusty singing of male voices belting out “We’ll Meet Again,” “I’ve Got Sixpence,” and endless other songs. Young men, mixing memories and premonitions and feeling a bittersweet sense of loss. They’d remember this evening, aswim in Labatt’s beer in the humid, smoky lounge of an elderly clapboard hotel in a town in the middle of nowhere. The sound of the singing, the feelings of belonging, the premonition of never knowing another moment like this: that night would tug at the heartstrings for . . .

My sleepy mind lost its grip; the thread slipped away and vanished. I woke up Sunday morning and saw the Governor Simcoe deserted. A sense of loss clung to me for weeks.

* * *

■ ■ ■

Musical prodigies like Mozart have no literary equivalents. The ear is a lightning-quick organ. Contrarily, the brain develops language only gradually: thus, the caves at Lascaux are studded with perfect animal cartoons—and no captions. Kid novelists are scarce. Françoise Sagan, anyone? That French writer hit the big time at age eighteen. She may have peaked early: none of her work after Bonjour Tristesse wowed the literary world.

My writing career began inauspiciously, with a sixth-grade class assignment to compose a fire safety essay. Before exposing my draft to the teacher and the class, I asked Mike to read it over. He’d barely started before his loud cackle contradicted my serious intent. A blunt question was the powerful opening line. “How would you like to loose your life?” I had written. I’ve seldom made a spelling mistake since.

The setback failed to quash my growing urge to write, an urge that accelerated the day I discovered Dad’s portable Royal typewriter where he’d stashed it on a closet shelf. Typed drivel gained five thousand times more authority than the same drivel written by hand. The act of feeding a page into the machine thrilled me: What would emerge when I finished? Mere twaddle, when it marched across the page in rigid straight lines of typeface, gained weight. Unlike a schoolboy’s lumpy scrawl, a typed page deserved attention and, until it was found to be senseless blather, respect beyond the dreamy hopes of a ten-year-old author.

The typewriter was a free pass into the sober world of letters. It forced me to imitate published writers, to advance my spelling, to pull back from uncouth language and sloppy-looking work. Typing elevated the writer; readers wouldn’t stand for careless scrawling. I loved the rituals involved: Rolling sheets of paper into place. Tapping the keys, watching each stroke pounded onto the page, then seeing intent magically turn into words and sentences. Hearing the little bell and nudging the next line into being with that perfect ergonomic carriage return.

My typing was done in brief bouts and called for stealth. Like a Free French operative hidden under the kitchen floor of a Paris boîte in 1941 furtively transmitting coded messages to London under the nose of the Gestapo, I dreaded Dad discovering his machine in my sweaty hands. He didn’t need to officially forbid anybody sharing his Royal. Sharing wasn’t in his DNA.

* * *

■ ■ ■

Any kid could trace Mickey Mouse off a comic book page. Far fewer kids could write down quickie stories for classmates facing a deadline with their scribbler pages blank. Soon enough I was doing a brisk trade in book reviews and story-writing exercises in English class. A dime bought a single-page review of Tom Sawyer or Kidnapped. A quarter got a taut story—setting, plot, characters, the works. A sideline to this sideline was a page of lurid U.S. Civil War battlefield carnage in blue ballpoint ink, price determined by body count.

Literary fame was clearly nigh. If a ten-year-old author churned out neat little mini-novels that sold on the spot, how much more fame and coin, in increments of more than two bits, was waiting up there with the big boys? Protecting my bottomless ignorance, I shoved under the rug such concerns as the fact that I was unpublished. Nor was I as informed as an author ought to be about the odds of a ten-year-old boy being contracted to write a bestseller. So, like any famed writer needing to shield himself from rabid fans and autograph hounds, I decided I needed a nom de plume.

The Bell Telephone directory for Simcoe yielded as many noms as a plume-pusher could ever require. I drove Mother nuts, day after day, reciting likely choices. Eventually, the hunt was abandoned: the town directory fatally lacked the brand of aristocratic French and Russian names, sleek with grandiosity, that my pre-success now pre-justified.

* * *

■ ■ ■

At an early age books and magazines pumped high-octane stimulation, available nowhere else, into my cerebral cortex. My vocabulary ballooned. My horizons expanded. Reading at that hungry developmental stage, when your head is an empty vessel, acts almost like a drug: the more you ingest, the more you want, until it’s become a full-blown craving and is ultimately needed to maintain mental equilibrium.

The McCall living room shelves were a cross section of literature of the late twenties and early thirties: Michael Arlen, Edmund Wilson, H. L. Mencken—a variety of literary genres. I read them all (well, to be honest, I passed my glazed eyes over some), from Hector Bolitho’s deferential biography of King George VI to the weirdly comic, including Don Marquis’s unjustly neglected Archy and Mehitabel and an early effort at parody by Corey Ford, Salt Water Taffy, with witty photographic illustrations. Our parents had taste and discrimination, not the result of being wellborn or highly educated but because curiosity had driven them to reading, whereupon reading led to learning, kindling a passion that never faded, indeed remained a necessity and a pleasure for as long as they lived.

Their mutual attraction, arguably aided by each discovering the other’s intelligence from reading books without pictures or talking vermin, began in Simcoe High School. Their dueling class newsletters, one edited by Tom McCall and the other by Peg Gilbertson, put aside classroom news and useful school-related fare. They featured feigned personal attacks, disguising tender feelings within insult-charged cannonades of mockery and teasing throughout the school year.

I still ponder why our parents’ literary enthusiasms were withheld from us. Mike, Hugh, and I—with Walter coming up fast—had forsaken comic books; all of us wanted reading that meant something. We were soul mates to our parents, and it would have immeasurably enriched our reading lives to talk books with Mother and Dad. It would also have helped close the vast gap of intimacy between our parents and us. Given Tom and Peg McCall’s allergies to meaningful contact with their offspring, maybe that explains this disinclination. Living among the collected wisdom and sophistication conveyed by a sea of books, in a rare small-town home where the life of the mind was recreational and educational, we were excluded from the blessings of such good fortune. Left to devise my own solution for enlightenment, I plugged away regardless. I kept reading for selfish pleasure. Consequently, I didn’t know what an autodidact was until I’d become one.*

I grew up assuming that writing and drawing originate in the same synaptic boiler room and split only when one or the other is deliberately left behind. I couldn’t (and even today can’t) grasp why it is that—despite the fact that writing and drawing share so much creative DNA, so many neurons flashing through the same network of muscl

es, veins, and nerve endings—this creative duality coexists so seldom that the term “writer/artist” almost always means “self-described hack.” (Which is why “I’m an artist-writer” has been voted the dreariest charade of all time.)

I’ve virtually always written and drawn simultaneously and can offer no scientific reason for it. I’m an artist and a writer—maybe better defined as a writer who draws and paints. My first act in making an illustration is to pepper a page with free-form, stream-of-consciousness phrases. Not notes, exactly, but blurts about color rules, the mood, things to avoid: in sum, pep talks to myself. A blank page is a terrifying thing to an artist. Words help diminish the fear of losing oneself in a vast white emptiness. Or maybe that’s just me. At any rate, I can’t get traction without this step.

An insufficient art education bars me from enjoying museum shows and retrospectives. After a lifetime of toiling in art, that admission should haunt me. It doesn’t. I’m the sum total of a bundle of instincts, and gaps and mistakes in shaping them. That mess is my style.

How Did I Get Here?

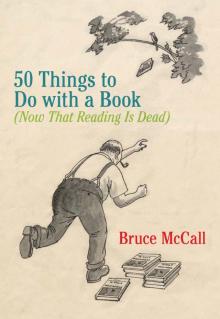

How Did I Get Here? 50 Things to Do With a Book

50 Things to Do With a Book