- Home

- Bruce McCall

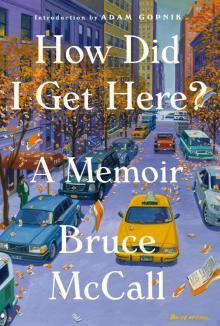

How Did I Get Here? Page 16

How Did I Get Here? Read online

Page 16

* * *

■ ■ ■

The J. Walter Thompson agency ranked at the time as one of the biggest ad agencies in the world and was also America’s oldest. Ford Motor Company aside, its list of clients included Pan American World Airways, Kodak, and a slew of category leaders with big ad budgets. Joining J. Walter felt similar to enlisting in the army: an entity so big and decentralized and balkanized that nobody really knew its direction and purpose; a hierarchy of ranks and layers and the inevitable bureaucracy; senior brass you never saw, running a machine so complex it left them no time for the foot soldiers.

Morale didn’t often thrive in an agency this busy and this big. If J. Walter had a point of view and a value system about its mission, defining itself to potential clients and uniting employees behind a single and singular philosophy, I never saw or heard about it. I got no sense that this bothered the brass. The sole gesture of team spirit I ever experienced at Thompson was the day every employee got a brass medallion the size of an oatmeal cookie commemorating the agency’s hundredth year. Before the end of the day I’d, er, misplaced it.

As with every big agency of the day, JWT’s creative department roughly consisted of three component parts: a few killer talents, then journeyman writers and art directors below them, and at the bottom, drones, hacks, and juniors. The stars generated a goodly portion of the agency’s multimillion-dollar campaigns, and bidding wars to land these creative talents were fierce. There were never enough of them to meet demand: job-hopping was worse than in the current NBA. Meantime, journeyman agency writers, art directors, and TV producers handled the bulk of the creative work. Most stayed in place for long periods, assigned to two or three accounts and juggling the workload. Longevity on an account assured continuity and made certain creative people indispensable. The most effective of these solid performers earned positions of responsibility as copy chiefs, art supervisors, and group heads. Drones and hacks served as permanent spear-carriers. Some hovered on the border of competence. Few were happy about their futureless futures, working on a diet of drudgework that kept them unsung. But most of them realized that their talents were modest, recognized that they were never destined for big bucks in big jobs, and remained at their humble stations because they couldn’t earn the same money anywhere else.

Standards of advertising quality are elusive, but that they exist can be easily proven: give a drone or a hack the chance to make an ad for the current campaign for his or her account. The result is guaranteed to be off-strategy, and either stupefyingly dull or incomprehensible. Drones and hacks don’t have what it takes to be journeyman creative contributors. That’s why they’re drones and hacks.

* * *

■ ■ ■

Μy work experience at Thompson forced odious comparisons to Campbell-Ewald. I had no complaints that my reception lacked fanfare; no ceremony was involved. A brief encounter with a graying fussbudget nominally in charge of staffing gained me a health-insurance booklet and other spellbinding paperwork, whereupon the fussbudget’s secretary marched me through a bewildering series of halls. Finally I was ushered into a grotto of an office for two and left to my fate. My roomie, a mystery man on the Ford account whom I barely saw, devoted most of his day to loud, prolonged, profane telephonic tiffs with his missus, quacking in his Brooklyn-accented Donald Duck voice. The office doorway stayed open to the jabber, hallway disputes, and foot traffic passing by.

At least twenty-five people—of whom I met maybe ten—swarmed around the Ford creative room. An island in the middle of the space provided office cubicles for a few toilers.

Organization of the Ford creative group was evidently inspired by Charlie Chaplin on that assembly line in Modern Times. This proved inimical to creative inspiration, or at least to my creative inspiration. Individual brilliance was rendered pointless by the fact that the group functioned on the monkeys-and-typewriters principle: every writer in that glorified boiler room was commanded to churn out headlines and body copy for the same Mustang or Galaxie or Falcon newspaper ad. Every writer’s efforts were tendered to Bert, the copy supervisor. There ensued the briefest of pauses while he speed-read the few dozen candidate pages. Then, minutes later, came individual summonses to Bert’s preposterously cluttered little cubbyhole for his feedback.

Bert was the first workaholic I ever met or worked under. He would have dismissed the work ethic of Ebenezer Scrooge as featherbedding. He could scan two days’ worth of headlines in two minutes flat and zero in on their flaws. His critiques were muttered in a rapid-fire monotone out of the side of his mouth. Bert wasn’t lavish in his praise or anything else. He was all business, all the time. He approached making ads as a grim, joyless exercise: boiling the fat out of every line of copy, driving his writers to the wall with orders to go back and whip up more, more, more headlines and text.

Bert favored—insisted on—sugar-free copy. His unsubtle approach was to grab readers by the scruff of the neck and rush them through a volley of bullet points to the bottom of the page. He begrudged a wasted word. The resulting ads were as hardworking and unsentimental as Bert himself. The romance of language, the allure of the automobile, gooey emotion of any kind, diluted the hard sell and earned Bert’s quick dismissal. As the self-declared poet laureate of driving’s pleasures, I chafed and fumed at the diminishing of copy to brisk word clusters cleansed of every space-wasting adjective and adverb.

After the rich banquet of Corvette, writing on the Ford account was lukewarm gruel. The environment was boot camp. The pressure never let up. I perforce got to be adept at the art of compression. I learned to clip, chop, tighten, push away the sludge to shape a selling argument to the buyer’s needs. It felt good to be good at it, but it wasn’t enough. Gloomy Bert, taciturn, ever-preoccupied Bert, had no time to be lovable or even likable. He and I had zilch in common. It didn’t surprise me when, a few years later, Bert, all energy and edgy perfectionism, rose to CEO of J. Walter Thompson.

Fellow Ford copywriter Art Odell was the one close friend I made at J. Walter. He and I shared a penchant for satire and fed off each other’s subversive glee. The dreary routine in a corner of that impersonal place was relieved by our frequent cross-office exchanges: lovingly detailed drawings of spectacularly idiotic airplanes, parodies of our own Ford advertising (“Ford Fever Strikes—Whole Town Doomed!”), or whatever else struck us as worthy of ridicule. Art was gentle, pixieish, pathologically insecure, and a terrible fit in the advertising trade.

Six months in Bert’s blacking factory was all the learning I could absorb. I was feeling familiar pangs of restlessness. And with the statute of limitations on gratitude close to its expiration date, it was time to find a place more amenable than Ford, Bert, and J. Walter Thompson could ever provide.

Whereupon Kismet, a.k.a. the Good Fairy, enters from the wings and plants a big wet one on my kisser. Once more, all I needed to do in order to escalate to a better job and a richer life was to sit on my prat, twiddling my thumbs, until the telephone rang. And ring it did. My good friend Roger Proulx, a colleague from the Track & Traffic days (he wrote some pieces for the magazine), had just heard from a friend that Mercedes-Benz was starting over in the United States and had hired Ogilvy & Mather as its advertising agency.

* * *

■ ■ ■

A week later I was head copywriter on Mercedes-Benz at Ogilvy & Mather. The best cars in the world, linked with the best advertising agency in the world. A job that hundreds of copywriters would gladly walk through fire to attain had dropped into my lap. With luck like this, who needed initiative or savvy?

The Ogilvy in Ogilvy & Mather, David, had elucidated a radical advertising philosophy in his 1963 bestseller, Confessions of an Advertising Man. His confessions mostly concerned his success. From first page to last, D.O., as he was known by everyone in his agency, hammered home the doctrine of rationality. He extolled it as the long-forgotten and neglected principle of advertising all goods and servi

ces. He had studied advertising as a researcher and had measured its effectiveness. Real-world advertising clobbered trendy “creative inspiration.” He wrote copy that flirted with the outrageous. He spun adages that stuck in the mind as inarguably true: The more you tell, the more you sell . . . People don’t buy from clowns . . . The consumer isn’t a moron, she’s your wife. David Ogilvy codified advertising relentlessly, persuasively. He compiled his findings on every tiny detail and rained hellfire on lazy writers and art directors who ignored them. He elegantly railed against advertising creativity untethered to a selling proposition. This enraged adland’s liberals and made him a pariah to most of them. Understandably, it also began to attract clients. The reassurance Ogilvy’s doctrine offered—stern, objectively proven facts versus creative hot air and guesswork—clicked. Relief at last for CEOs’ constant agonizing that the millions they’d invested in advertising had essentially always been a form of gambling. His axioms sided with their contempt for know-nothings. Ogilvy’s philosophy refuted the shibboleth so many clients subscribed to: “Half of our millions of advertising dollars are wasted every year—but damned if I know which half!” David Ogilvy knew.

David himself was a major part of Ogilvy & Mather’s attraction: a tweedy, pipe-puffing, deep-voiced British aristocrat. He was the best public speaker, the wisest pundit, the most fearless critic of humbug and smarm and self-indulgence. No one had written and spoken more frankly and persuasively about advertising in the history of the genre. His prose was bone-clean and unaffected, E. B. White on speed, not a comma wasted, pompous Englishisms shunned. As in all fine writing, his was crystalline. The reader of an Ogilvy ad entered a deluxe selling machine, was royally entertained, and on exiting was punch-drunk on the merits of the product. And grateful for the ride.

Accomplished individuals can be major pains in the ass, so it was lucky for D.O. that most of his flaws actually burnished his image. He had the ego of a Shakespearean actor. He was a ham who loved the spotlight. His quick temper frightened people. For D.O., arguments were a kind of exercise: should he lose, he wouldn’t admit it. Log enough time around him and you’d discover that deep behind the charm of that upper-class British persona lurked Willy Loman in a Bond Street suit and red suspenders. He aimed his keen intellect, writing talent, and passion for truth at selling, and nothing but. Scorning those ambitious to write books, he huffed that their very presence was a bloody waste of space.

I had read Confessions a couple of years before joining O&M. Detroit taught me nothing about making successful advertising. His book threw me a lifeline. As it did to would-be experts everywhere with a lust to know the inner secrets of selling. Within this modestly smallish volume was a virtual step-by-step tutorial on how to make not only effective but distinguished advertising. David Ogilvy became my hero. Single-handedly and almost overnight, he levered advertising—at least, his advertising—out of the clichéd demiworld of lowbrow hucksterism. Advertising didn’t have to be a near-criminal conspiracy. It could be tasteful, honest, and useful. People of intelligence and high cultural standards, like—well, for instance, like me—rallied to the Ogilvy cause. A certain snobbery inevitably attached itself to the agency’s image, a faint trace and no more. (Americans profess contempt for snobbery while secretly enjoying the hints of class superiority that define it.)

The O&M offices at Forty-Eighth Street and Fifth Avenue felt on first acquaintance like those of a prosperous London legal firm. Prosperous indeed: advertising growth was exploding, and Ogilvy & Mather was just beginning an overseas expansion. In New York, creative people occupied not cubicles but offices. Ubiquitous crimson carpeting suggested the House of Lords more than the tackiness typical of much ad agency decor. I was flattered and proud just to walk into the building every morning before eight and work until six or seven in the evening.

David Ogilvy himself stomped through the halls, ten times more formidable in person than in prose, the ultimate headmaster. It wasn’t in him to waste time or words. His physical presence scared people when, as was his frequent habit, he dropped into your office with no warning. Today he’s carrying a proof of the ad you’ve just written.

“Tell me what you think that headline is actually saying,” he barks. You assume he’s being critical, but your defense is waved off. He’s already moved on to some other topic.

“How do you talk to a millionaire?” He is serious. You blurt out some bromide. He talks through and over it. He hasn’t heard you because he’s answering his own question:

“I’m a millionaire,” he says, “and what difference does it make when you’re selling me this gadget, or that car? I want the same information as anybody else!”

He turns to leave. Over his shoulder, he snaps: “Copywriters use the most unctuous, ornate, silly language when they’re selling to millionaires. They think they have to suck up to the rich and they end up sounding like butlers. Fools!”

And as suddenly as he barged in, he barges out. Such impromptu visits, after the Great Man had exited (without a goodbye, as was his wont; not rudeness but shyness, because he didn’t know his quarry’s name and felt bad about having to ask), were sometimes embarrassing to the unready and the dull-witted. For the rest, they were bracing enough to cancel the visitee’s panicky initial impulse to soil his pants.

Wealth and breeding defined David Ogilvy. He’d be at ease in 10 Downing Street or the White House. He never condescended to his agency staff or his audience. He was allergic to pandering. This reversed the reflexive cynicism of advertising tradition so that most O&M employees forgot the dogface’s ritual resentment and jealousy of the big boss. They admired, respected, and were awed by him.

In presentations he cast an almost hypnotic spell. He dealt with captains of industry as an equal and wasn’t afraid to bluntly tell them unpalatable truths about their products and reputations. He once harangued a convention of American automobile dealers because research had found that the public rated them dead last in trustworthiness and related virtues. When he finished his hiding of the audience, they treated him to booming applause.

A David Ogilvy new-business pitch was brilliant theater, featuring his inimitable self. The crux of his talk (sans notes, naturellement) was a parade of charts that incorporated the fruits of deep, imaginative, and meaningful research. These charts steamrollered tired and dated beliefs. It was difficult to quibble with such clear proofs, but somebody always did. Watching this poor fool’s challenge get politely smitten by David’s verbal broadsword was an entertaining moment before the lights flickered back on and the meeting ended.

Imaginary headlines swirled around in my head as I commenced settling into life at Ogilvy & Mather: “High School Dropout Makes Good” . . . “‘Comeback Kid’ Proves Doubters Wrong” . . . “McCall Earns Huge Raise on First Day.” Alas, McCall was never able to sunder the copywriter–art director division. No writer, by an ancient tradition that was frequently reinforced, was ever allowed to so much as suggest a layout or fiddle with any graphic element. The custom also held that no art director should presume to tinker with a copywriter’s words. That rule was almost never tested, because the average a/d read as little as possible. Unfortunately this applied to ads for which he was responsible. “Functional illiteracy” is too strong a term, but some a/d’s came close. My art background cut no ice with them. I could draw better than any a/d I ever worked with (a fact, not a boast), but any suggestion I made was rejected out of hand. My heart was scalded when a stoneheaded a/d botched a graphic element in favor of a second-rate solution.

Mercedes-Benz had been slow to plant itself in the postwar American car market. The three-pointed star hadn’t exactly been a household name in prewar America, either. The brand was associated with fading images of something German, stuffy, well made, and expensive. With that to work with, O&M had to position Mercedes-Benz against the “luxury” segment of the U.S. market. A Mercedes-Benz was expensive, and that ended its similarity to the America

n concept of luxury—literally, more than is needed. In the American vernacular, luxury meant more trim, more padding, more weight, more size, more gadgetry. These “luxuries” didn’t make a car better, just gaudier. The price of a Mercedes-Benz bought no superficialities, only superior technical solutions and the superior performance they guaranteed.

A car designed for German conditions and a different automotive culture had to compete with the longer, lower, roomier, sexier, higher-powered American luxury sedan, like Cadillac or Lincoln. Mercedes-Benz simply outflanked the entire U.S. luxury car precept and positioned its automobiles as an almost grimly rational alternative to the traditional American luxury car. The benefits could be seen and felt. Like a cold shower, the range and value of these benefits shocked the prospective buyer into seeing a Mercedes-Benz not as a status symbol but as a superior machine. And made that buyer wonder why such machines weren’t American. The Monroney sticker (government-required manufacturer’s specs and price details) on a Mercedes window delineated a sound investment in driving efficiency, practicality, quality, and longevity.

How Did I Get Here?

How Did I Get Here? 50 Things to Do With a Book

50 Things to Do With a Book